Ten years ago, venture capitalist Marc Andreessen wrote his now famous article titled “Why Software is Eating the World” in which he described a dramatic shift whereby every business would eventually (and inevitably) transition to operating on software-based systems, delivering goods and services either digitally or via the internet.

Over the last decade, Andreessen has largely been proven correct with one industry after the next getting upended by new entrants, who have often started narrow in focus but have ultimately been able to achieve extraordinary reach as a result of having been designed on top of infinitely scalable software infrastructure.

One industry that has been noticeably resistant to this change has been the financial industry and, more specifically, private equity, with the most dominant players in the space today still being largely the same groups that helped create the industry more than thirty years ago.

To understand why the industry has been more resistant to disruption and why that is finally changing, it’s helpful to first understand how the industry works.

The private equity value chain

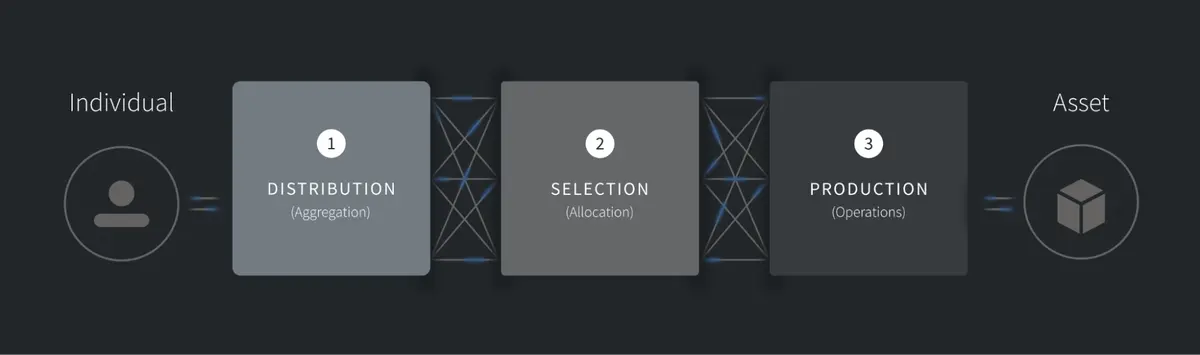

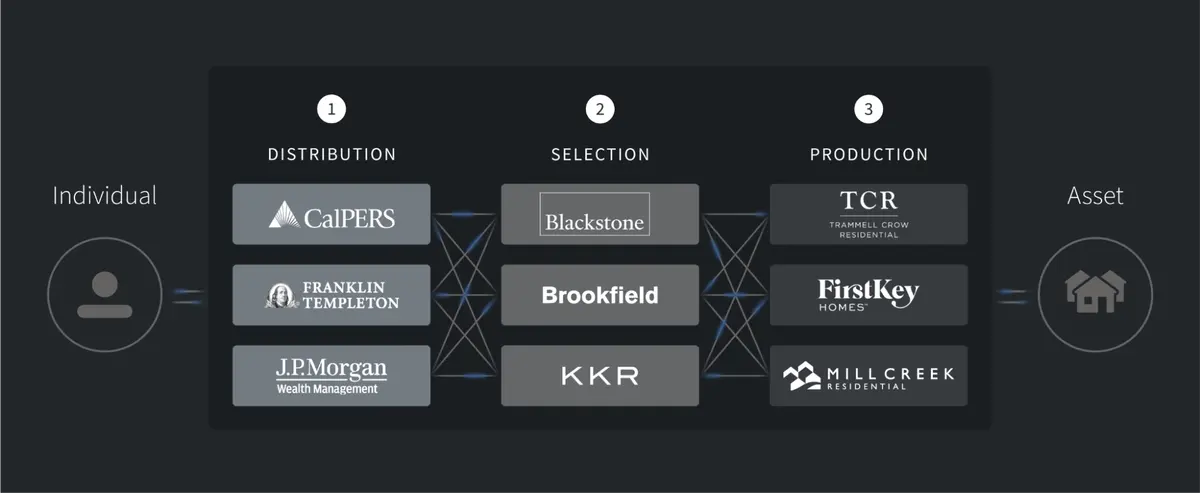

The private equity industry, like most industries, can be represented in its simplest terms as a “value chain.” In other words, it consists of a series of steps that go into the creation of a finished product, from its initial design to its final delivery to the customer. The chain identifies each step in the process at which value is added, including the sourcing, manufacturing, and marketing stages of its production.

In the instance of private equity specifically, the process consists of taking dollars (i.e., savings) from an individual and moving them into an asset (such as real estate) and then, after some process of value creation, delivering back to that individual the investment returns produced by that asset.

We describe the value chain as being made up of three unique steps:

- Distribution (or aggregation)

- Selection (or allocation)

- Production (or operations)

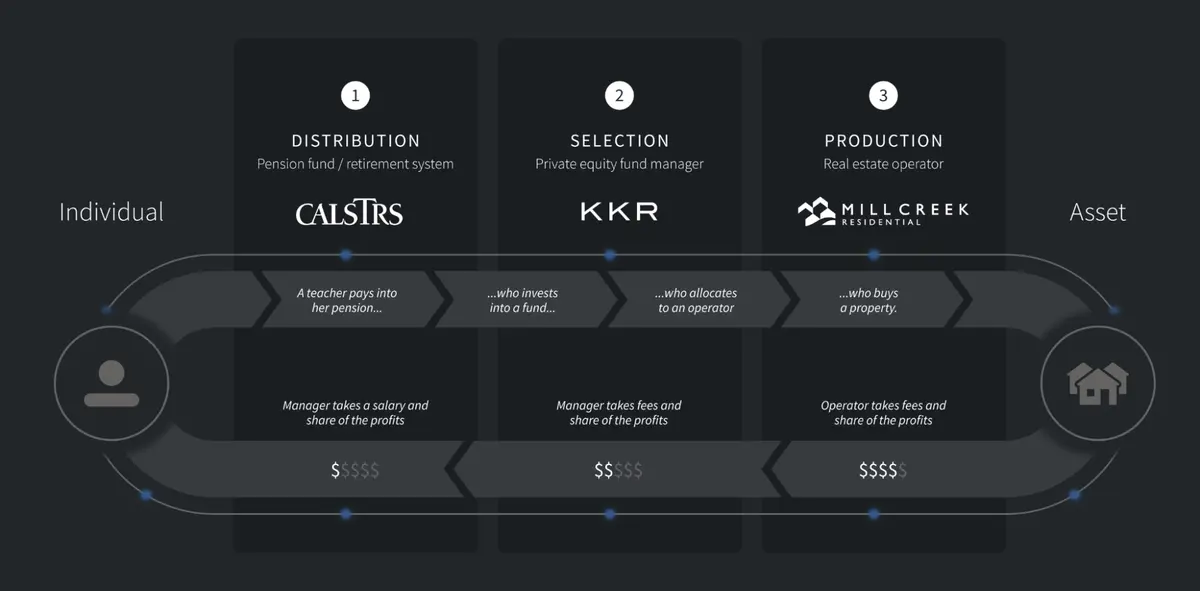

(1) Distribution

The distribution (or aggregation) step is where the savings of many individuals are pooled together for the purposes of investing. This can be via entities such as pensions, endowments, and sovereign wealth funds, or it may occur via investment advisors such as RIAs or wealth managers, who manage money on behalf of their high-net worth clients. In either case, an intermediary acts to aggregate the savings of many individuals and create one large source of investment capital that must be deployed in order to generate returns.

(2) Selection

The selection (or allocation) step is where investment managers (groups such as Blackstone, KKR, and Carlyle) raise money from the aforementioned institutions (i.e., aggregators) for specific predefined strategies: for example, investing in newly constructed apartment communities in the Southeast. These fund managers then assemble a portfolio of investments by selecting specific partners on the ground (i.e., operators), whose job it is to execute on the specific predetermined strategies, and allocating to them a portion of the fund’s total capital.

(3) Production

The production (or operations) step is the final link in the chain, where the operating partner — in this instance a real estate company — takes the capital allocated to them from the private equity fund and uses it to acquire and then operate properties that generally fall within the aforementioned investment strategy or theme. Eventually, the operating partner sells the asset and returns the profits back to the private equity fund manager who in turn returns it to the institution that initially invested it.

Along the way, at each of these steps, the actors involved charge a number of different fees for the work they are doing. These fees generally fall into one of two buckets: (i) recurring fees that are charged annually, such as asset management fees; and (ii) one time fees, the largest of which is the profit-sharing or incentive fees that are charged at the end of the investment lifecycle where both the real estate operator and fund manager each keep a share of the profits earned from the investment.

Visually, the process generally looks something like this:

Value chains and specialization

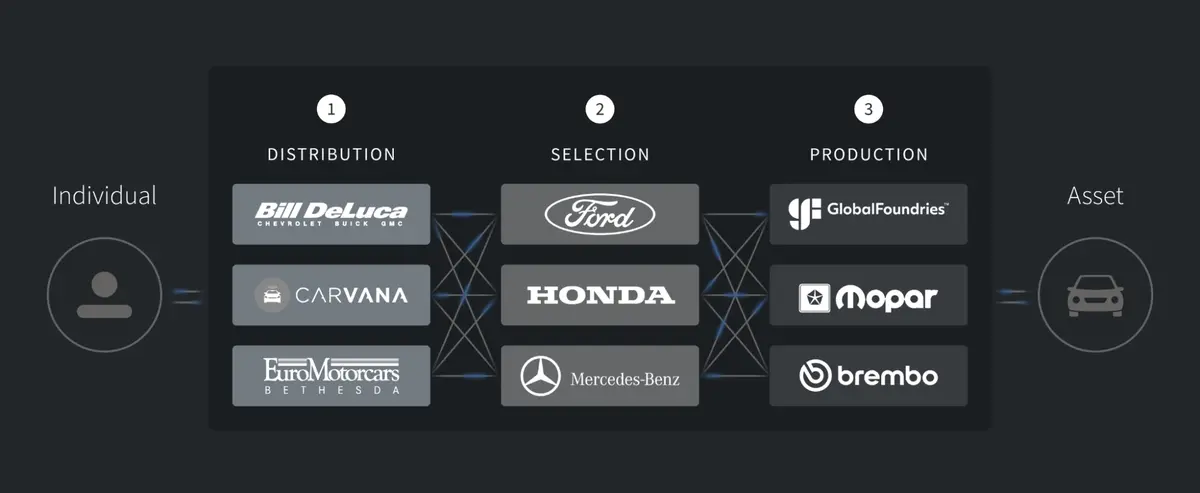

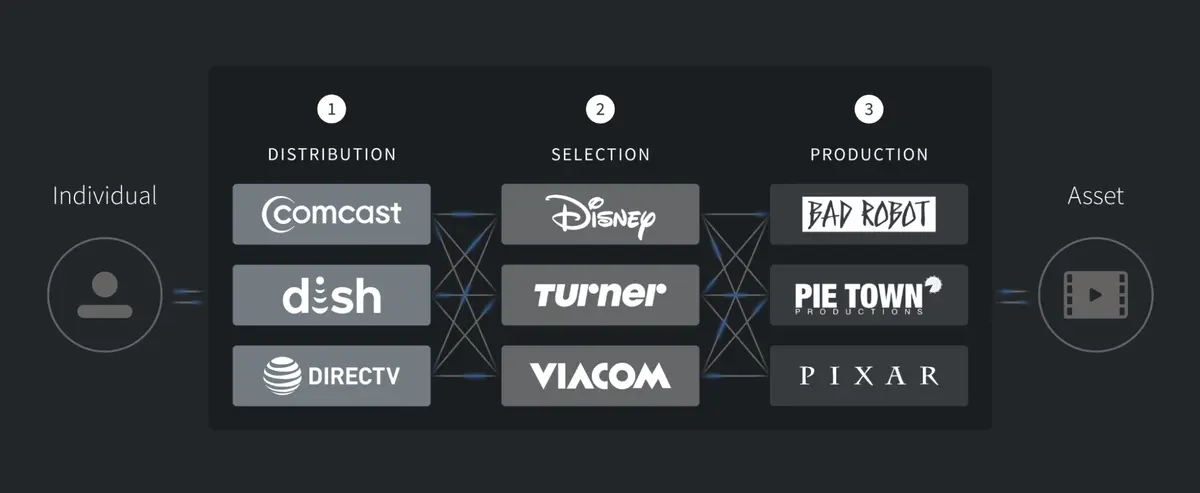

Generally speaking, as industries grow they tend to follow the same patterns. They begin small as a result of some new innovation, which in turn creates a new market. As demand in the new market increases, the industry starts to scale to meet that demand. Over time, with more entrants into the market and greater competition, the focus shifts from scaling to increasing efficiency. And to deliver this efficiency the players in the industry become increasingly specialized and more segmented, with each company focused on excelling at only one step in what becomes the larger industry value chain.

This pattern can be seen over and over again across numerous industries, from retail to automotive to the entertainment industry and to, of course, private equity.

Automotive industry

Entertainment industry

Private equity industry

When value chains get disrupted

The problem with this increasing specialization and segmentation is that it tends to result in more rigidity. Each participant becomes increasingly dependent on the other players around them to deliver value, and, as a result, they collectively become unable to operate outside the ecosystem. The industry, once mature, becomes highly efficient but also highly inflexible, making it difficult to innovate and therefore highly susceptible to disruption.

Of course, the nature of disruption is that it is as inevitable as it is unpredictable. Though difficult to forecast when and how new technologies may impact an industry, over a long enough time period it becomes increasingly certain that at some point some change will occur, and the result of that change will be profound, most often leaving the previously dominant companies left playing catch-up.

Integration

The idea of integrating value chains (or vertical integration, as it has been referred to during different periods) is not new. Originally implemented by industrialists like Carnegie, Rockefeller, and Ford, it has evolved and taken different forms over the course of many decades.

The act of integrating different steps in the value chain often gives the companies that do it a unique competitive advantage, allowing them to simultaneously reduce costs and/or provide a greater experience for their customers, while also capturing more of the value and profits generated for the company itself. (For background, we suggest readers explore the work of one of our favorite thinkers on this topic: Ben Thompson from Stratechery, who coined the term Aggregation Theory.)

As Andreessen foresaw and Thompson notes, the advent of the internet created a powerful new tool that in particular upended the distribution step of the value chain for nearly every industry. Whereas physical infrastructures and high-entry costs had previously created a moat to new entrants, the internet allowed almost anyone to distribute, sell, or share many goods and services at nearly zero cost.

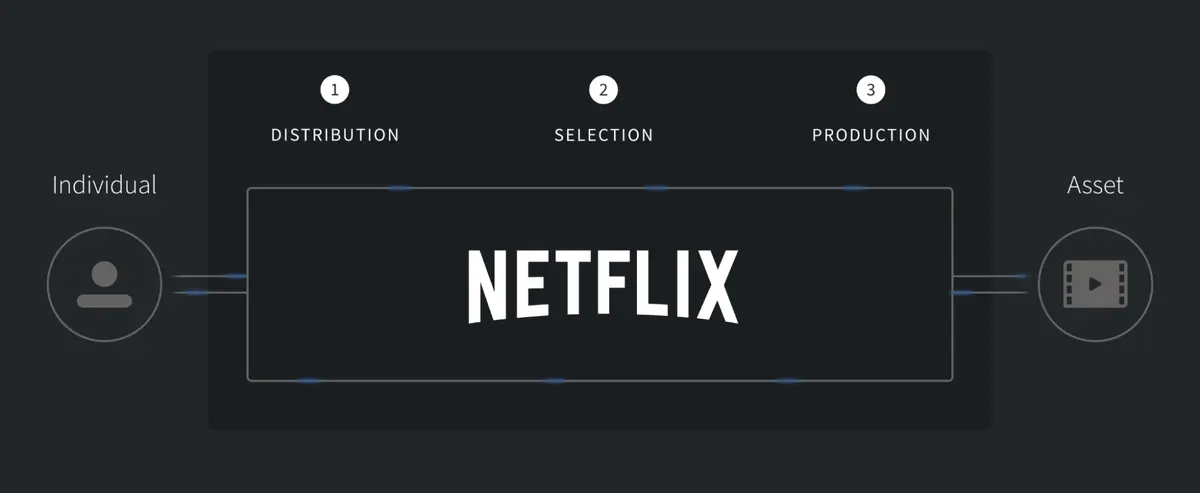

One of the clearest examples of this has been Netflix’s disruption of the entertainment industry. When Netflix launched their streaming service they created a new distribution channel outside of the large cable providers and movie theaters. This new distribution channel provided a better experience for customers — namely, control over what you wanted to watch, when you wanted to watch it. Once Netflix established the distribution channel they were able to integrate other steps in the value chain, ultimately becoming their own production studio and creating their own exclusive content, specifically designed for the new channel (e.g., niche shows, full season drops, and the advent of “binge watching”). The model was so successful that at one point CEO Reed Hastings said their biggest competition was people needing sleep; of course, Disney, HBO, and others all ended up having to follow suit, copying Netflix’s distribution strategy in order to compete.

Unlocking real estate private equity

The modern real estate private equity industry evolved in the early 1990s as an aftereffect of the Savings and Loan Crisis of the late ‘80s. As Schecky Scheckner put it on a recent podcast episode, “It was the Big Bang” (of real estate finance).

At the time, the internet was still in its infancy. Email was not something anyone used. There were no websites, let alone universal mobile phones. There was no means by which someone could easily access information about trends in certain markets or data around rental rates. The real estate market generally was fragmented and inefficient, with local knowledge and expertise residing exclusively in the hands of local experts on the ground.

It was around this paradigm that the real estate private equity model evolved, along with the fee model to go with it — a model focused on the inherently laborious and extremely inefficient nature of the business and the need, of course, for local partners.

Nearly thirty years later, in the early 2010s, after all the advancements in new technologies and yet another financial crisis, the industry itself had experienced little to no meaningful evolution. The cost structure whereby nearly 50% of the returns generated by the assets were being taken by intermediaries remained unchanged, even though the world itself had not.

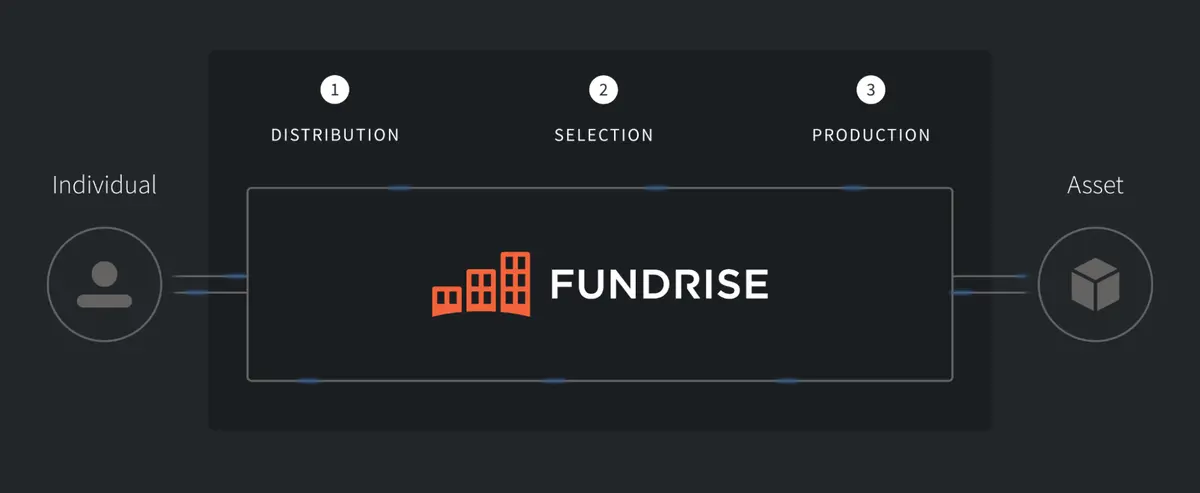

It was within this context that we launched Fundrise and set out to disrupt and dismantle the existing system.

Much like Netflix, we started by building out a new internet-based distribution channel, not only dramatically expanding access to the asset class but breaking the hammerlock control held by the large institutions such as the pension funds, wirehouses, and large wealth managers.

We paired this technology infrastructure with regulatory innovation, utilizing new offering structures to create public access to private assets.

The result was a significantly less expensive, more direct, and more transparent way in which a significantly greater number of individuals could actually get access to institutional quality real estate private equity.

Much like Netflix, we’ve leveraged this initial innovation to work our way through the value chain, replacing both the traditional fund manager and more recently the real estate operating partner… in both instances not only bringing that work in-house but also utilizing the same technology-first approach and software engineering expertise that allowed us to recreate the “distribution step” to redesign the traditional methods for owning and operating real estate necessary for the “production step.”

In the end, we’ve created (to our knowledge) the first and only fully integrated, end-to-end private market investment platform. A single value chain built entirely on top of proprietary software (such as Cornice™, Basis™, and Equitize™) that aims to deliver the elusive 10x product… which, in this instance, means a potentially 10x cheaper and more efficient model for investors to access alternative investments.

As has been true in so many other industries, we believe the effect of this fully integrated operating model will not only lead to these types of cost improvements, but also unlock new ways in which we can invest and create value for our customers that otherwise would not be possible, work that is already well underway, which we expect to continue to roll out later this year and into the next. In the long run, as Marc Andreessen predicted, we believe the integration itself becomes the competitive advantage that allows us to provide a completely unique and super experience for our investors that compounds over time.